DeepPlastic: Detecting Marine Debris with Computer Vision

Every minute, two truckloads of plastic are dumped into our oceans. That's over 10 million tons per year - a number so large it's hard to conceptualize. But the real challenge isn't just knowing that plastic is out there. It's finding it.

The traditional method for quantifying floating plastic involves dragging a manta trawl through the water, physically collecting debris, and then analyzing the samples in a lab. This works, but it's slow, expensive, and labor-intensive. You can't scale manta trawls to monitor the entire ocean in real-time. Without better sampling methods, we're flying blind - unable to identify high-concentration garbage hotspots or track how plastic moves through ocean systems.

This research started with a simple question: could we use computer vision to detect plastic automatically, in real-time, without physical collection?

The Approach

We focused on the epipelagic layer - the uppermost zone of the ocean (0-200 meters) where sunlight still penetrates. This is where most positively buoyant plastic accumulates, riding currents and gyres across the globe. It's also where autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) can operate effectively with onboard cameras.

The workflow we developed is straightforward:

- Deploy an AUV equipped with a camera and an onboard deep learning model

- Scan the water column, capturing images continuously

- Run inference in real-time to detect and quantify plastic debris

- Use the detection data to guide physical removal or map concentration hotspots

The key constraint was that the model needed to be small and fast. AUVs have limited compute resources, and we needed near-real-time inference speeds to be useful for both mapping and active cleanup operations.

Building DeepTrash

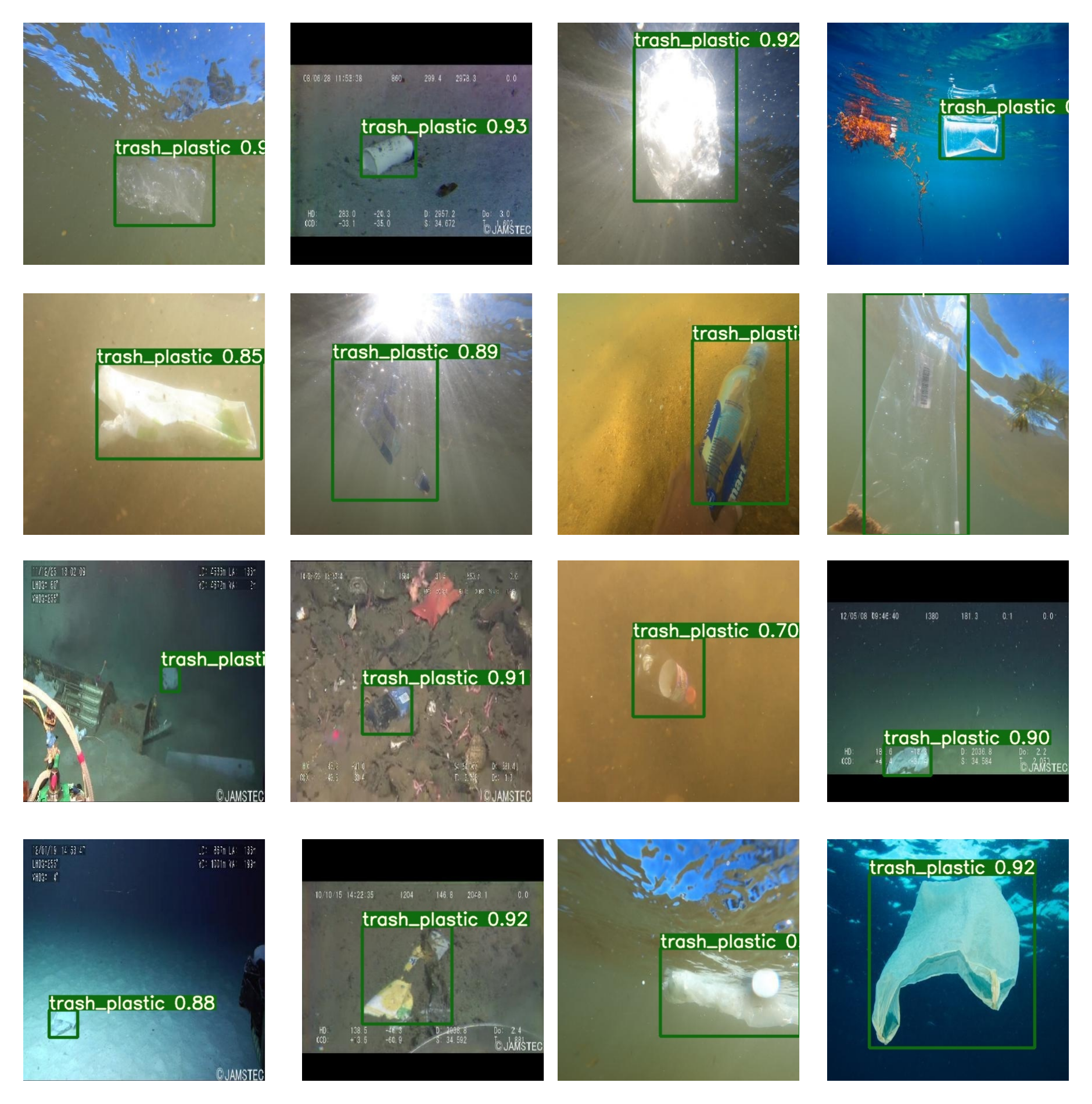

The first problem was data. There's no ImageNet for underwater plastic. Existing datasets were either too small, focused on the wrong environment (deep sea floor vs. epipelagic), or not publicly available.

So we built our own. The DeepTrash dataset contains:

- 1,900 training images (60%)

- 637 test images (20%)

- 637 validation images (20%)

The images came from multiple sources:

- Field collection from Lake Tahoe, San Francisco Bay, and Bodega Bay in California

- Internet scraping from Google Images (less than 20% of the dataset)

- Deep sea imagery from the JAMSTEC JEDI dataset

This diversity was intentional. Underwater conditions vary wildly - turbidity, lighting, water color, debris types. A model trained only on clear Caribbean water would fail in murky coastal environments. By including images from multiple sources and conditions, we aimed to build a model that generalizes.

The challenges of underwater imagery are significant. Light attenuates differently at depth. Particles scatter and absorb, reducing contrast. Colors shift toward blue-green. These same problems eventually led me to work on synthetic data generation and image enhancement - but for this project, we worked with the imagery as-is.

Model Selection

We evaluated several detection architectures:

- Faster R-CNN: A two-stage detector known for accuracy but slower inference

- YOLOv4: Single-stage detector, faster but still computationally heavy

- YOLOv5: The newest iteration at the time, optimized for both speed and accuracy

Our goal was a model with high precision that could run in near-real-time on embedded hardware. False positives matter - if the model mistakes coral for plastic, it undermines the entire system. But speed also matters - a model that takes seconds per frame is useless for a moving AUV.

The Results

YOLOv5-S emerged as the best performing model:

| Metric | Value | |--------|-------| | Mean Average Precision (mAP) | 0.851 | | F1-Score | 0.89 | | Precision | 85-93% | | Inference Speed | ~9ms per image |

For comparison, Faster R-CNN achieved 77-80% precision but with significantly slower inference. YOLOv4 was faster than Faster R-CNN but still couldn't match YOLOv5's speed-accuracy tradeoff.

YOLOv5 was also 20% faster than Faster R-CNN on average, which translates directly to more images processed per dive, more area covered, and better detection rates.

One specific issue we encountered with Faster R-CNN: 3-5% of coral formations were misidentified as plastic. This false positive rate was unacceptable for real-world deployment. YOLOv5's higher precision largely eliminated this problem.

Deployment Considerations

Beyond raw performance, YOLOv5 had practical advantages:

Accessibility: The repository was well-documented with clear setup instructions. Our team included researchers who weren't deep learning specialists, and they could get the model running in under an hour.

Versatility: Within a couple of days, using only 3,000 images without augmentation, we were able to adapt the model to work in lakes and rivers. Despite murky water and challenging conditions, detection accuracy remained high.

Simplicity: Training was straightforward. Result checking was manual but manageable. The entire pipeline from data to deployment was achievable without specialized ML infrastructure.

These factors matter for real-world impact. A model that requires a team of ML engineers to deploy isn't going to see widespread adoption in marine conservation.

Limitations

This work has clear limitations:

Dataset size: 3,000+ images is substantial for this domain but small by general computer vision standards. The model's generalization to unseen environments and debris types remains uncertain.

Single class: We treated all plastic as one class. In reality, different types of debris (bottles, bags, microplastics, fishing nets) have different removal strategies and ecological impacts.

Epipelagic only: The model was designed for surface and near-surface detection. Deep sea plastic detection is a different problem with different challenges.

Static imagery: We worked with still images. Video processing introduces additional complexity around tracking, temporal consistency, and handling motion blur.

These limitations motivated follow-up work on generating synthetic training data to expand dataset diversity without expensive field collection.

The Team

This research was a collaboration across institutions:

- Gautam Tata (Primary Author) - Machine Learning Research

- Sarah-Jeanne Royer - Marine Scientist, Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Sarah-Jeanne's expertise in marine debris and ocean chemistry was invaluable for grounding the ML work in real-world marine science.

- Olivier Poirion - Jackson Laboratory

- Jay Lowe - Machine Learning Research

Resources

The full paper, code, and dataset are publicly available:

- Paper: DeepPlastic: A Novel Approach to Detecting Epipelagic Bound Plastic Using Deep Visual Models

- Code: github.com/gautamtata/DeepPlastic

- Dataset: DeepTrash on Zenodo

- Demo Video: YouTube

If you're working on marine debris detection or want to build on this research, everything is open source under Creative Commons.

Citation

@misc{tata2021deepplastic,

title={DeepPlastic: A Novel Approach to Detecting Epipelagic Bound Plastic Using Deep Visual Models},

author={Gautam Tata and Sarah-Jeanne Royer and Olivier Poirion and Jay Lowe},

year={2021},

eprint={2105.01882},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CV}

}

Conclusion

Marine plastic detection is a hard problem, but it's a solvable one. The bottleneck isn't the machine learning - current architectures like YOLO are more than capable. The bottlenecks are data, deployment infrastructure, and integration with physical cleanup operations.

This work demonstrates that real-time detection is feasible with small, efficient models running on embedded hardware. The DeepTrash dataset provides a foundation for others to build on. And the approach - using AUVs with onboard inference for scalable ocean monitoring - offers a path toward the kind of global-scale plastic tracking that's currently impossible with physical sampling methods.

The ocean is vast and plastic is everywhere. We need automated eyes in the water to find it.